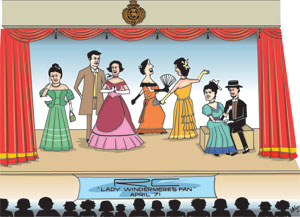

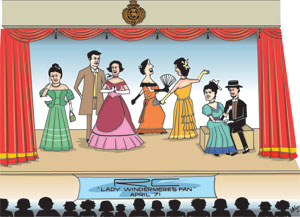

Wildly excited the boys were that Sunday, April 4, in 1971, almost exactly 40 years ago. It was the eve of a public performance in Colombo of Lady Windermere’s Fan, the famous Oscar Wilde comedy. The play was to be put on by the drama society of a leading boys’ school, its young men dressed up as Victorian ladies and gentlemen, and it was to be performed at a leading girls’ school round the corner. The boys had been rehearsing the play for months, and had their lines and cues in place, and their costumes – top hat and tails and frilled and flounced Victorian gowns – cut and re-cut to fit. The stage was set. Props, lighting, posters, handbills and programme, and at least one newspaper preview – all had been taken care of. And there was no shortage of help from students eager to escape the classroom.  |  | | The dress rehearsal for the play that was aborted. |

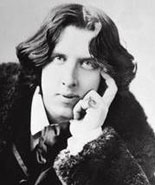

If any were to wonder what Royal College, Colombo was doing with a comedy about 19th-century England (Oscar Wilde’s hit play was first performed in 1892, at the St. James Theatre, London), their attention might have been drawn to the school itself – a solid red-brick Victorian institution, dating back to 1835, just two years before Queen Victoria ascended the English throne. The school was a Victorian monument. The idea of performing a Victorian play came from a young Cambridge graduate from England, who was spending a year in Ceylon teaching English. He believed that mouthing the best of English dialogue was one way to teach quality English, and everyone agreed that Oscar Wilde’s poised and cadenced lines were as close to perfection as English dialogue could get. Also, curiously, Oscar Wilde was the vogue in those years, in the ’60s and early ’70s. The school debate society was in full swing, and it venerated Wilde, the renowned wit who had a ready and memorable answer for every occasion (“if we could give Oscar Wilde-type replies, the opposition would be floored’’). Oscar Wilde was read studiously and furiously in the hope that the Irish writer’s verbal brilliance would rub off at inter-collegiate debates. It was hard not to be fascinated by the personality and legend of the great and disgraced Irish writer and entertainer. Schoolboys have a natural sympathy for anyone who flouts the rules, and the outrageous Oscar broke many of the rules of his time. Wilde’s flamboyance and effrontery, his moral and social anarchism, had huge appeal to certain English-medium educated teens. How could one not warm up to a famous/notorious adult who said such provocative things as, “I never put off for tomorrow what I can possibly do the day after” (a sterling excuse for late homework); “There is no such thing as a moral book or an immoral book. Books are well written or badly written. That is all” (the assurance you needed when secretly reading banned classics), and “The only way to get rid of temptation is to yield to it” (solace for the guilt burdens of pubescence). Oscar was the schoolboys’ hero – at least for those five hectic, hyperactive months of Lady Windermere’s Fan. By the evening of Sunday, April 4, 1971, all details to do with the production were in place. There was only one problem, a serious one. Lady Erlynne, a crucial part played by the fair “Tweeny” Abeyewardene, had started to lose “her” voice some weeks earlier. The problem was thought to be a combination of laryngitis and nerves, and Lady Erlynne was urged to visit both a general practitioner and a psychiatric counsellor. He/she did, but the condition persisted. Everyone was getting jittery. One especially nerdy Fifth Former with a reputation for quoting Wilde at every turn was given 48 hours to memorise the part of Lady Erlynne. A couple of days ahead of Monday’s opening, Lady Erlynne’s voice came back, albeit a bit hoarse and masculine-sounding.  | | Victorian monument: Royal College, Colombo, was established in 1835. |

And while all this was happening, far behind the scenes, in the greatest secrecy, unknown to Lady Windermere, the rest of the cast, the school, and the greater world outside the school gates, there was another, bigger drama unfolding. This drama was of epic proportions, with a plot of nation-shaking consequence, and it had a cast of thousands. It had been rehearsed for months in scattered and distant parts and was ripe for public “performance.” The players would be young adults, about the age of the Lady Windermere set and a little older. This national drama had been scheduled to open the following Tuesday, April 6, but due to unforeseen developments the “opening” was brought forward by a day to Monday, April 5 – which was also Lady Windermere’s big day. While the Lady Windermere set went to bed early that Sunday night and had nightmares of missed cues and forgotten lines, the cast of the bigger drama were up all night, fanning across the country, arming themselves, and taking up positions. By noon the next day, Monday, April 5, telephones were ringing in every home and office. There was trouble in the country. Big trouble. The state radio announced that there would be an islandwide curfew, starting at 5.00 PM. Lady Windermere would have to take a seat and await her call. What followed that day, and in the days and weeks after, was one of the country’s most extraordinary, and most bloody, episodes. The Marxist-inspired Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) took the country by surprise, overpowering police stations around the country, and challenging the regime and its ill-prepared armed forces. The ’71 insurrection, the first offensive of the JVP, would be crushed decisively. But that Monday, we all thought the revolutionaries would be in the city by nightfall. The curfew was lifted a month later. A tense moment in history had come and gone, but it would be a long time, years, before the magnitude of the uprising and its quelling would be understood. By May 1971, normal life in the country had resumed and students were going back to school. Lady Windermere was invited to return to the stage at Royal College, Reid Avenue. By that time, however, the cast and crew had lost much of its enthusiasm for the play. Nevertheless, it was decided not to let all the hard work and preparation go to waste, so rehearsals were resumed, although half-heartedly. This time there would be no public performance; just one school show. The preview that appeared in the Daily News on April 3 had kind words for the production, while observing that it was “off-putting to see Victorian ladies built like rugby players.” The afternoon school performance was something else altogether. The entire staff and student body were present, filling the hall up to the balcony and spilling into the corridors. The cast and crew had secretly arranged to have a little fun during the matinee, in collaboration with Mr. Oscar Wilde. The plan was to give a farcical, fast-forward version of the play, with lines rewritten to include in-jokes about the teachers and the prefects. There were other jokes as well, gags aimed at unsuspecting members of the cast. Props were mischievously manipulated. A glass of ginger ale that was to substitute for whiskey was in fact a solution of vinegar and salt mixed with something stronger, causing a sputtering, spluttering effect on the actor who had to drink it. At another point, a framed photograph was brought out for inspection, but instead of the expected Victorian lady’s portrait there was a centrefold ripped out of Playboy magazine, the sight of which caused the startled actor to fling the object across the stage.  |  | "If you want to tell

people the truth, make them laugh, otherwise they'll kill you".– Oscar Wilde. Irish dramatist, novelist, and poet (1854-1900) | Oscar Wilde: revolutionary in his time. |

The audience guffawed, not so much at the dialogue and antics as the spectacle of fellow schoolboys attired in sweat-soaked Victorian outfits, while the cast exchanged little knowing smiles. Teachers familiar with the play knew something was wildly askew, but went along with the jollity. The sense of things going hilariously out of control was growing by the second. One act of daring almost cost the actors their school careers. Cigars mentioned in the original script had been deleted from the school show. The actors, however, had pinched a handful of Havanas from a cigar-puffing parent and smuggled these on stage inside their waistcoats. During a strictly men’s scene, the young swells not only produced the cigars, but lit and smoked them. The audience roared. There was one highly graphic and original moment that took all by surprise. The resplendent Lady Erlynne was to make one of her exits, but instead of going out backstage, she descended the steps of the platform, and stepped outside, her back to us, the sunlight shimmering on her pink chiffon glory. And, as if departing forever, she glided through the garden and out of sight. It was a surreal, unscripted, cinematic and strangely inspired moment. That afternoon was entertaining and baffling; it was wild, and wilder than Wilde. It was the talking point for months. All that stylised dialogue, and all those protestations of love addressed by boys to cross-dressed boys was amusing and bemusing. Forty years later that long-ago afternoon retains its queerly absurdist, anarchic, and anachronistic pitch. Meanwhile, there was the other, bigger drama taking place, on another scale – the long moment between the cancelled April 5 performance and the school show. In that month of curfews and suspended animation, when schools closed and we all waited, the sound of gunfire pattering in the distance, between 15,000 and 50,000 young revolutionaries – the figures vary – were eliminated in a ferocious crackdown across the country. These revolutionaries were young adults a little older than the young men involved in Lady Windermere’s Fan, and they were targeting the urban elite who were enjoying privileges not available to them. One of the key privileges was language: while the elite had access to English – at home, in school, in the community – the rest, represented by the young revolutionaries out in the country, had little or no English. Lady Windermere’s Fan was symbolic of a small privileged class nurtured on English. It was an explosive play, in a sense, with the potential to fan a revolutionary’s fury. If there had been no curfew on April 5, 1971, and the opening night of Lady Windermere’s Fan had gone as scheduled, we might have had youthful revolutionaries storming the city that day. Their first destination would likely have been the fancy precints of Cinnamon Gardens. We can imagine them marching through Colombo Seven, smashing up the posh cars lined up along Flower Road, and charging into the Ladies’ College Hall, where they might have either caused great harm, to persons and property, or sat with the rest of the audience to watch the play. If that had happened, a bit of comedy with boys dressed as women might well have had a softening, calming effect on the revolutionaries. Who can tell? Comedy is the other side of tragedy, and vice versa – the two being the opposite faces of the same intricately patterned Chinese silk fan. The cast and the crew, and their roles, then and now The Director: Anthony Gates, a volunteer service officer, who had just graduated from Cambridge University, spent a busy year in Ceylon, from 1970 to ’71, working as an English Language and Literature teacher and producing plays at Royal College, Colombo. Having lived outside the UK for many years, he is currently the Chief Justice of Fiji. THE CAST: Lady Windermere – Imtiaz Muhsin: Founder and Managing Director, Crescent International School, 1985-2006; currently developing an innovative website - Encyclopedia of Sri Lanka Through Postage Stamps (www.stampodepedia.com) Lord Windermere – Dr. Rohan Fernando: General practitioner, based in Melbourne, Australia Lord Darlington – Hari Gunasingham: Chief executive officer (CEO) of an IT company in Singapore. Hari produced the artwork that appears on the cover of the programme for Lady Windermere’s Fan (shown at left). Mrs. Erlynne – Dr. Siridev (Tweeny) Abeyew-ardene: General practitioner, based in Sydney, Australia Lord Augustus Lorton – Suresh Gunasingham, CEO of a Sri Lanka-based civil engineering firm Mr. Dumby – Capt. Mehran Wahid: Ex-ship Captain, currently working for a German shipping company with close ties to Sri Lanka Lady Jedburgh – Michael Matthysz: Director, CMS Garment Technology, Sri Lanka Mr. Cecil Graham – Chulan Weeresinghe: Qualified Accountant based in the UK since 1973; maintains an interest in rugby, cricket and music Lady Plymdale – Christopher Parakrama: Director of a Sri Lanka-based software company; former president of the Sri Lanka Arts Centre, and past president of the Sri Lanka Computer Vendors Association, and the Sri Lanka Association for the Software Industry. Christopher was also Sri Lanka’s first schoolboy national chess champion. Parker, the Butler – Christopher Storer: Retired from the ship industry, having worked overseas for many years THE CREW Among the backstage crew in 1971 were: C. I. Gunasekera Jr: Qualified Accountant, based in the UK since 1972 Dhammike J. Wedande: Director, Asia Siyaka Devinda R. Subasinghe: Former Sri Lanka ambassador to the US and Mexico, currently serving on APCO Worldwide's International Advisory Council (IAC), as a consultant on emerging markets and foreign policy Zaki Alif: Director, Stassen Group, Sri Lanka | | | Anthony Gates | Imtiaz Muhsin |  | | | Dr. Siridev Abeyew-ardene | Capt. Mehran Wahid |  |  | | Devinda R. Subasinghe | Zaki Alif |

|